In her native South Africa, forensic scientist Dr Desiré Dalton experienced wildlife in ways which most of us can only dream about.

Her work has varied from being in close proximity to big cats such as lions and cheetahs, to identifying new species of bats. She has gone to work with international agencies involved in wildlife conservation.

Desiré spoke to Talking Teesside to share a little about her wild past – and how she’s involved in ongoing research and work to ensure the future protection of wildlife.

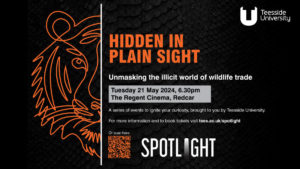

She will also share insight into the murky world of the illegal wildlife trade at a free talk on May 21 at The Regent Cinema in Redcar

African penguins look very regal, but they smell terribly of fish and like to bite. I still have the scars.

Watching cheetahs run at full speed is a thrilling experience, and a baby elephant up close is the cutest thing you will ever see.

Lions are terrifying up close, even when anaesthetised. If they wake up, you don’t have to be the fastest runner, just not the slowest.

My work has involved investigating the evolutionary history of animals, and I have identified new species, as well as identifying and investigating diseases in wildlife.

I have helped to identify a new bat species in West Africa. I also discovered that pangolin are related closer to cheetahs than anteaters. I described for the first time a white stork hitting a plane at 3,353m above ground level and have identified a hybrid animal which resulted from a kudu and a nyala.

Where did your love for animals come from?

I have always had a love of animals. My affinity for them was sparked by Charles Darwin, who showed that animals, just like humans, possess emotions – even the more complex emotions such as jealousy.

They have a sense of humour, they feel wonder and curiosity, they feel pain. I wanted to help animals, to make a positive difference in the world that we share.

I decided to study zoology and biochemistry because of my love of animals, however at that point, I did not have a clear career path in mind. The one thing that changed everything was my first lecture in genetics.

The idea that a simple code of four letters – A, G, C and T – in DNA shapes how we look, our personality – and that one simple change can have devastating consequences – was fascinating to me.

How did your work start?

Through my PhD post-doctoral fellowship at the South African National Biodiversity Institute – formerly National Zoological Gardens of South Africa – I was able to combine my two loves, animals and genetics. This set me on my career path into wildlife conservation.

The focus of my work in South Africa was wildlife population genetics. I would use various genetic tools to determine population structure and genetic diversity. If wildlife populations are genetically different from each other, they need to be managed separately. If they are genetically the same, corridors should be maintained so that the animals can mix.

Genetic diversity also identifies which species and populations will be able to respond to future environmental change. By identifying populations with low genetic diversity, you identify animals that are at risk of extinction.

I additionally conducted research on human mediated hybridisation, which occurs when two different species or subspecies breed together. In general, hybridisation is a threat to one of the species and needs to be monitored closely.

I was also responsible for the provision of wildlife forensic genetic services to the South African Police Service and Botswana forensic laboratories.

What does your work involve?

In forensic cases, my work has involved identifying species, matching samples, such as matching blood on a knife with an animal that has been killed in the wild, and identifying the geographic origin of the animal.

I’ve provided a genetic service to wildlife farmers and conservation agencies, and I assigned parents to offspring, identified hybrid and pure animals, and provided management recommendations.

I also identified species involved in bird strikes with planes. Bird strikes are a serious problem that can lead to serious damage to planes. By identifying species commonly involved in bird strikes, work can be done to develop measures to prevent them.

I’ve also been involved in conducting food authentication tests, ensuring that what is on the label of food products is correct.

What’s in store for the future?

Although I continue to find my research very interesting and fulfilling, I also felt that it was time to inspire the next generation of scientists, which led me towards an academic career. Teesside University is unique as it has a very diverse set of students from various countries and backgrounds, thus what I teach has far-reaching consequences into the future.

By bringing my life experiences to the classroom, I can hopefully inspire students to find their passion. I truly enjoy seeing a student grow to a mature and confident individual. It is very rewarding giving students a helpful hand to get them on their career path and then getting to cheer them on from the sidelines.

Hear Desiré share more insight into her work and delve into the illegal trade in wildlife in the second of Teesside University’s Spotlight series of talks taking place across our region. Book a free ticket.

Take a deep dive into how highly organised criminal syndicates use sophisticated methods to take advantage of transport networks, the internet and social media to trade in animals and plants. This talk examines the magnitude of this practice and looks at what is being done in attempt to curb this harmful trade and protect our wildlife.