We’ve pivoted. We’ve shifted. We’ve migrated. Take your pick – but whichever one you go for, university academic staff have moved our face-to-face teaching online to allow us to support our students during our various COVID lock-downs. But now a number of friends and colleagues who work at other universities have been told to start thinking about increasing the online delivery of degree courses. And they’ve got the summer to do it all in!

Now when I was Associate Dean (Learning & Teaching) in SSED (which seems like a lifetime ago even though it was just 6 months…), I had TUOLE in my portfolio. TUOLE is our online engineering offer and we were (probably still are) pretty much the biggest HEI provider of online Pearson HNC and D qualifications in the country. By some distance. And added to that, of course, I also co-developed and co-deliver the Forensic Archaeology and Anthropology Future Learn course with the splendid Prof Rebecca Gowland and the International Committee of the Red Cross which in its first run had over 6000 learners and this time has over 4500 learners. So I think I have some credibility here when I talk about managing online learning. And what’s my take-home? That’s easy. Creating and delivering effective online teaching is a lot fucking harder than it seems.

Our online MOOC has 6 sessions with each one providing between 1-3 hours of learning material and engagement. It’s basically a Netflix one-shot mini-series. Have a guess at how long it took us to develop this for the first run? Congratulations to anyone who guessed ‘5 months’! And then we spent another 2 weeks updating the content for this second run. And that’s without including the time that the ICRC invested in it too. Although to be fair, Prof Gowland did the vast amount of work on this and as ever, I mostly just floated about. Even taking into account my work-shy nature, the timescales are much longer than people assume. This will inevitably be the case when you are creating brand new content and especially so if also translating field/lab-based skills onto an online platform. The Archaeology Department at Durham spent significant funds on creating the 3D models and videos for this course.

It’s really important to remember that what most of us have done now is not really online education. It’s rapidly plonking PowerPoints onto VLEs and doing Zoom seminars to supplement them. It’s a hasty replication of what we normally do. Is it effective? We don’t know. Do the students like it? We don’t know. Is it scaleable? We don’t know. So why are my colleagues being encouraged to deliver more standard degrees online? I suspect because it seems cheaper than the usual model. However a key question is where or not there is a market demand. I’m not entirely sure, but at the moment I’d argue not. We know that some students are feeling short-changed about this enforced shift which is why we are seeing petitions for reducing fees. Plus if this was the model students wanted, the Open University wouldn’t have been in such financial peril. Remember that big argument for developing MOOCs as they were the future? We’re hardly tripping over them now, are we? Future Learn has developed a model for success, but the fee structure in place will not work for universities (they’re basically free for the learner).

So here are some initial thoughts based on my experience, which I’ve jotted down for you while I wait in a 40 minute queue to get into the supermarket:

- Don’t forget that not everyone has a suitable PC to cope with super exciting online courses. We also know from experience that reliable internet connectivity is not something everyone has. Internet capability is also affected when say, your kid secretly watches four hours of anime on Netflix when you’re trying to have a Teams meeting. For example…

- Remember that some people want to leave the house! Some students and staff want the experience and structure that an on-campus experience provides. And to separate work from home. Or, you know, enjoy human contact. Not me, obviously, I can’t stand any of you. But other people.

- People do the online learning at different paces. Some do a little every week, some blitz large chunks all at once. This flexibility is great but you’ve got to bear this in mind when setting engagement activities, such as online seminars.

- Oh, and non-continuation rates are huge. They’re much larger than for on-campus delivery and the reasons for this are complex, but include home and work situations, additional financial challenges and the lack of face-to-face reminders of requirements.

- You’ve got to remember time zones! I had a heart attack on the first Monday morning of the first run when I saw tens of comments already because I forgot that the day begins earlier in other parts of the world. Learners come from all over the planet and so comment and engage at all times of our day.

- This also means that students may not be working 9-5 UK time. So emails can come All. The. Time. The boundaries of the normal working day blur. So you have to be strict otherwise it’ll gobble up all your time.

- Open access only! A key requirement for Future Learn courses is that all references etc must be open access. And actually this is a great philosophy generally as it really opens up new research to all. But! It’s actually still very hard to find open access articles for the topics you want, especially for books. Those that are open access also often derive from Western Europe or the US, and so there are issues surrounding the decolonisation of the curriculum to consider. In the UK, all academics dump their work on Institutional Repositories which is super, but less helpful when you want to highlight the work of other academics. Which usually I don’t, because I love to self-cite. For our second run we reached out to some journals to arrange open access for some content for the duration of the courses – so thanks to the Journal of Forensic & Legal Medicine, Antiquity and Forensic Anthropology.

- How do you cater for those with additional support needs or physical disabilities? We’ve been working through this issue currently with our online learners who have various forms of visual impairment. This needs to be considered when creating the online provision, not after.

But! And it’s a big but (snigger), online delivery can be fantastically inclusive and innovative.

- We know that many of those taking our MOOC live in isolated regions without access to higher education, or have childcare demands, or are housebound. The MOOC has allowed them to connect with leading research and academics on their own terms.

- It is so much easier to balance with work. We have seen that in the range of forensic and police practitioners on the MOOC in the first run, and with healthcare professionals in this second go. But I also saw this with the TUOLE offer which catered from engineers working in remote regions, on oil rigs and so on.

- Online teaching can remove some of the inherent heirarchies that we see when students are in a room with the lecturer at the front. It can be more informal and less intimidating for learners.

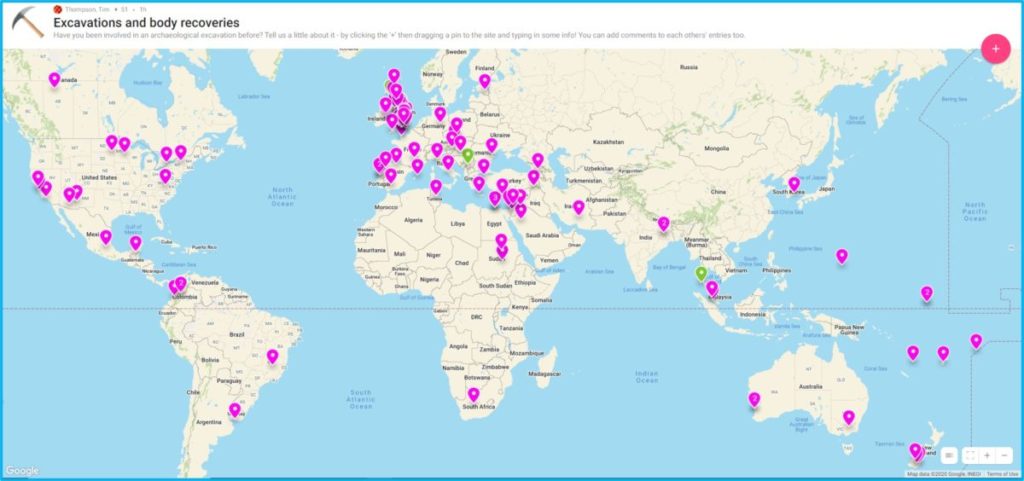

- Our Future Facing Learning initiative at Teesside has been really helpful with the MOOC, especially in this second run. For example, we’ve now got Padlets integrated into the course – including the one below which we use with our learners to share experiences of undertaking archaeological or forensic fieldwork involving human remains.

The current forced move to online provision does open up some great opportunities for academics. Personally I’m excited about the possibilities of reaching a wider audience of learners and in how we can further engage with digital tools to bring more external expertise to our students. We also need to see whether some of the lessons we’ve learned over these couple months can change how we run module assessments or committee meetings. I’m not convinced that we’re about to see a wholescale transformation of HE, but I can see some exciting enhancements and developments which should benefit staff and students.