This is the way – Baby Yoda and the power of the Force (on decision-making)

Categories Learning & Teaching

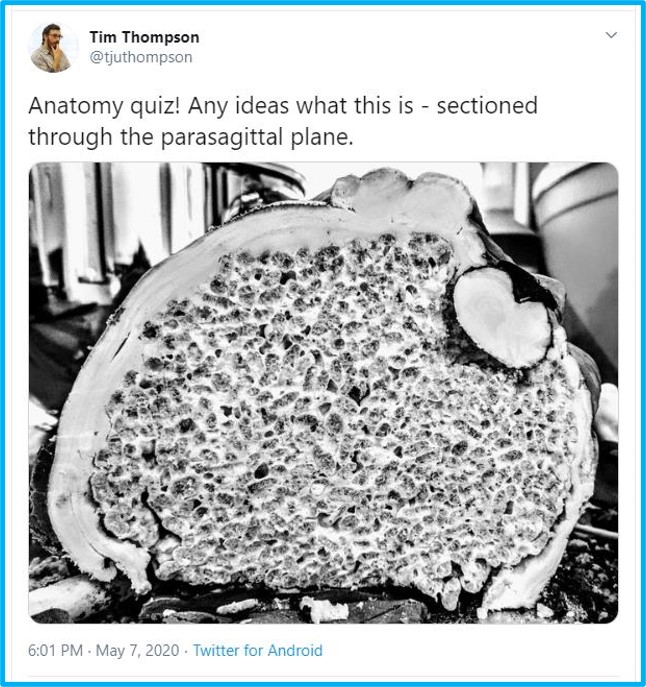

So, I’m a terrible person. Hilarious, but terrible. I was in the kitchen last week and saw the remnants of my youngest’s birthday cake (made by the uber-talented Becky Gowland) and I couldn’t help but notice how it looked a bit like a slice through bone. Obviously my next thought was to take a picture and put it on Twitter to see if I could trick everyone and thus make myself feel smarter than the masses. And then it took off a bit too much and as the evening progressed I kept looking at my phone with a strange and uncomfortable feeling. I think it was guilt. I rarely feel it so I can’t be certain. But to be safe, I ‘fessed up and thankfully everyone saw the funny side. Even after the public humiliation some of them went through.

Anyway, the whole thing got me thinking a bit as to why people were fooled. And I concluded that it was all because of cognitive bias. Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment and they come in a whole host of different flavours. In essence they are factors which influence how and why people make the decisions they do. They are particularly interesting and pertinent when we think about the application of forensic science, because this is supposed to be an objective, atheoretical approach to following evidence to the truth (spoiler alert: it ain’t).

Anyway, the key influencers for my false photo fun were that I tweaked the image to make it monochrome and cranked up the contrast so that it seemed like a medical image, I used technical terms in the description, it taps into a history of posting anatomical images like this and asking colleagues to chip in, and that it was sent out from a Professor’s social media account. People believed it was genuine because of the suggestive cues I intentionally included.

One of my areas of research and interest recently has been just this – how decisions are influenced and how they impact forensic practice. In the broader context, for example, last year we published the results of some work in the International Journal of Legal Medicine where we looked at how images influenced the conclusions reached by jurors where:

“The results show that the use of 3D imaging improves the juror’s understanding of technical language used within a courtroom, which in turn better informs the juror’s in their decision-making”

and prior to that I had some work published with one of my fab MSc students (Georgina Brookes) in the Journal of Forensic & Legal Medicine where we explored the interpretation of images on identification from tattoos noting that:

“The results [of the survey] indicated that the perception of tattoos has a high margin for error and interpretation”.

These are interesting because it suggests that there are things (in these cases, images) that can influence non-forensic folk acting within the forensic context. But we also know that there are various biases that affect forensic scientists themselves. In fact, the Forensic Science Regulator wrote in her report in 2015 that:

“many fields of forensic science include subjective assessment and comparison stages that are potentially susceptible to subconscious personal bias (cognitive bias). This in turn could undermine the objectivity and impartiality of the forensic process”

and the recent paper in Science & Justice by Dr Helen Earwaker et al highlights the steps needed to be taken to ensure that we have a:

“holistic approach to improving the transparency and reproducibility of decision making within forensic science”.

We have seen this repeatedly. So much so that the Innocence Project have produced an informative video on the impact of confirmation bias (one type of cognitive bias). In forensic anthropology, there have been a number of studies (mostly by Dr Sherry Nakhaeizadeh at UCL to be honest) that have demonstrated how contextual information influences the outcome of osteoprofiling. To explore the causes of this a little more, we have recently published our preliminary work using a Tobii eye-tracker to delve into the many steps that anthropologists make as they work through their osteoprofiling methods. Here we saw differences in the time taken to perform the analyses as well as where anthros looked on the skeleton. You may remember that we also presented some of our work using this approach on ancestry estimation with the splendid Dr Joe Hefner and Micayla Spiros over at MSU at the American Academy of Forensic Sciences conference back in February. You know, back in that time when we could still travel. Our thinking is that, by understanding how anthropologists apply our methods, we can take a step towards understanding the decisions we take along the way.

So there we are. Baby Yoda helping us reveal the manner in which forensic practitioners apply their methods and therefore on the potential conclusions of our analyses. So I guess we really could be as suggestive as Obi-Wan. That whole “These are not the droids you’re looking for” scene may not be that far from the truth.