Being asked to identify a crime suspect in a police lineup must be a daunting task for anyone – so imagine how difficult it must be for a child.

In this guest blog, Teesside University PhD student Georgia Wright shares insight into a research project she is leading which could revolutionise police guidelines when child witnesses need to identify crime suspects.

As part of my PhD research, I’ve been involved in developing best practice guidelines for child witnesses during police identification procedures. In other words, trying to find ways to make police identification procedures more accessible for children.

These adaptations aim to improve the ability of child witnesses to identify guilty suspects and reduce the likelihood of identifying innocent suspects.

When someone witnesses an offender commit a crime, and the person is not familiar to them, they are given opportunity – through a police identification procedure – to identify a suspect as the person they saw committing the crime.

Police identification procedures, also known as police lineups, are conducted by specialist police officers known as identification officers, with procedures designed to be fair to the suspect and safeguard against misidentifications.

In England and Wales, the preferred method of conducting a police lineup is through video identification.

This involves showing witnesses a series of videos of people who match the description the witness has given of the perpetrator. One of these videos will include the suspect, along with others taken from a special police force database for use in lineups, with a range of strict procedures in place to ensure fairness.

However, there are currently no standard protocols in England and Wales for adapting police lineups for child witnesses within current policies and guidelines. This means it is unclear to what extent the process can and should be adapted for when lineups involve child witnesses.

As a result, identification officers vary in how they adapt the procedure. This variation can lead to a national inconsistency in support for child witnesses.

My research is part of a wider project to develop evidence-based best practice guidelines which align with current policies and practices to help determine adaptations which could be made for child witnesses during police lineups.

My initial study involved interviewing Registered Intermediaries who have supported a child witness during a police lineup. Registered Intermediaries support the communication of children and vulnerable witnesses in the Criminal Justice System. This was to understand the experiences of Registered Intermediaries in supporting child witnesses communication during police lineups, and gain insight into any adaptations they might recommend during these procedures.

An advisory board was also set up to ensure the research aligns with current policies and practices, involving police officers from multiple forces, Registered Intermediaries and other expert stakeholders. I worked closely with the advisory board to identify which of the Registered Intermediary-recommended adaptations would be both practical and legally feasible.

My second study then focused on testing identified adaptations to assess impact on children’s ability to identify a guilty suspect. To ensure any study results could be applicable to practice, efforts were made to ensure the experiments were as realistic as possible. This was achieved by using mock police lineups, formatted and presented in the same way as real police lineups.

We carried out the study during the school summer holidays at the International Centre for Life (Life) in Newcastle. I attended Life for a total of 28 days over the course of five weeks.

I met potential participants and their families inside Life while they were engaging with the exhibits, and after introducing myself and informing them of the experiments taking place I asked if they would be interested in participating in the research project.

Some days I was also accompanied by my Teesside University Director of Studies, Dr Natalie Butcher, or a student research assistant, who helped in recruiting participants and ensuring that all the necessary paperwork was completed and stored correctly.

A total of 264 visitors aged between five and eleven took part in one of the four lineup experiments.

The participants viewed a mock crime video, completed a short shape-matching task, followed by one of the mock lineups. Participants and their families were then debriefed, when I explained the aims of the study and answered any questions, before they went off to enjoy their visit at Life.

Before viewing the mock crime video, the children who took part were not initially told they would be completing a lineup, as doing so may have led them to pay closer attention to the perpetrator’s facial features and improved their memory of the individual.

Real witnesses of crimes are mostly unaware of a crime before it happens, so withholding this information from participants further increased the realism of the study.

Four versions of the lineups were created to test three different adaptations and a control condition with no adaptations.

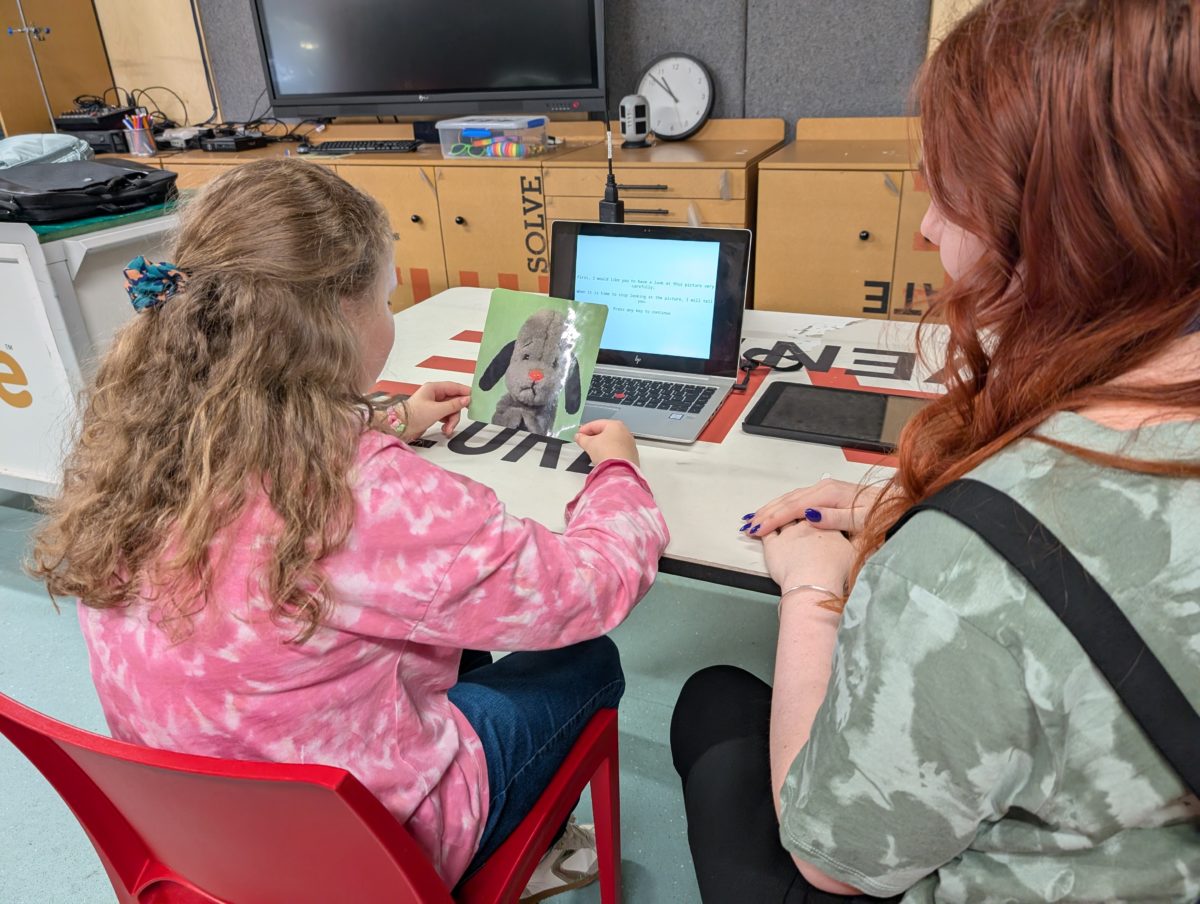

One involved adapting the instructions read to the witnesses to use more accessible language as recommended by the Registered Intermediaries. Another used a visual line of numbers placed in front of the participants so they could hold their finger on the number of the person they wished to identify. The third adaptation involved a ‘practice’ lineup using teddy bears, before conducting the suspect lineup.

I received an overwhelmingly positive response from participants and their families about the research. Many of the participants were very excited to meet a ‘real scientist’ and take part in a ‘real experiment’.

We frequently had a variety of interesting discussions surrounding the importance of the research and the possible impacts it may have for child witnesses. Parents and carers of children who took part in the research were particularly happy to hear their participation could help real witnesses of crimes, and applauded the involvement of young people in the research and fostering an inclusive environment.

My third study is currently underway, where I am testing the same adaptations under different conditions at local primary schools. We hope that the findings of both experimental studies, alongside the findings from the interviews with the Registered Intermediaries, will provide a clear understanding of which adaptations can and should be implemented for child witnesses.

Our recommendations will be transformed into an evidence-based best practice toolkit, designed to aid identification officers and Registered Intermediaries when supporting child witnesses during police lineups. The findings will also highlight the necessity of embedding specific and practical guidance within current policies and procedures to minimise national inconsistencies in support.

Accessible lineups could not only benefit child witnesses – they could also benefit the overall Criminal Justice System. Increasing correct identifications and reducing incorrect identifications will support both police investigations and justice overall.

Georgia Wright is a third-year PhD student based in the Psychology department of Teesside University’s School of Social Sciences, Humanities & Law.

Study with us. We’re proud to be University of the Year