Guest blog: Nikita Shepherdson

Autism is a neurological condition which affects how people interact, engage and communicate. Trainee clinical psychologist Nikita details her long journey to diagnosis and beyond, outlining her difficult childhood, mental health career and new best-selling book sharing the experiences of fellow autistic professionals.

Hi. I’m Nikita, and I’m a 28-year-old, autistic trainee clinical psychologist at Teesside University. It’s a short introduction, but I want to start my blog post by taking you back to an earlier time in my life…

I have always been a people-pleasing perfectionist at heart. From toddlerhood, I’ve wanted to get things right, but my understanding of social norms meant I was often in trouble.

Primary school was a nightmare for me. Year after year, my school reports speak of an inattentive child, making careless mistakes because she didn’t listen to instructions. But my mistakes were anything but careless; I desperately wanted to achieve and live up to expectations.

That’s the thing about growing up undiagnosed…

We might lack a medical label, but people will allocate other labels to you anyway. Mine were “bossy”, “annoying”, “sensitive” and “a drama queen”. The list goes on.

My childhood was saved by dancing. When I was little, I adored the clickety-clack of Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly’s tap shoes.

At age 6, I begged my mum to take me to dance classes. For the first few weeks, I would swing on the ballet barres while the teacher instructed the class. But dance was a place where I could be authentically me.

I was pretty good at it and loved it enough to practice hard. My parents even let me design the costume for my first dance competition. It actually looked like I created my own compression body suit (compression clothing can support those with sensory processing differences).

My senses were super sensitive – they still are. I loved the feeling of being squeezed and would always zip my jackets and hoodies right up to the neck. I would cover my ears to dampen sounds too.

It made shopping with me very difficult. I once caused a lockdown in Matalan because I became overwhelmed and hid inside a clothing rail. Everyone thought it was a missing child situation, but I was just hiding from the noise and bright lights.

Things got worse when I reached secondary school. I was sick of being in trouble all the time, so I wanted to turn over a new leaf. I gave my all to everything, put my hand up first (and enthusiastically) to answer questions and followed the rules avidly.

Tap dancing in the talent show as a new Year 7 sealed the deal for bullying over the next five years. Despite the fact I won, any hopes of fitting in were dashed from that point on.

I didn’t have friends or good mental health, so high grades felt like a trade-off. This became pressure in itself. I couldn’t keep up with the effort, especially factoring in my then-undiagnosed specific learning difficulties, which meant I had to put in maximum effort for average results.

So, I decided I’d had enough of trying. I started to get myself kicked out of class. I got to rid myself of pent-up sensory overwhelm frustration by slamming doors and mouthing off, and I was sent to isolation where I wasn’t bullied and people didn’t compare test scores. In fact, people there weren’t an issue at all.

Isolation was a room with a row of black-painted cubicles. You couldn’t see anyone on either side of you. You weren’t allowed to talk. It was dark, dreary, silent…bliss for this autistic child.

When I left school, my mum wanted me to do A-Levels, but I felt utterly done with formal education. I wanted to do a BTEC in Performing Arts.

For the first time, I had actual friends. My “drama queen” tendencies were normalised as “theatrical”, and my weirdness was a strength because I had no inhibitions when it came to drama and acting.

Overall, college was such a positive time for me. I landed the role of Cogsworth in the first production, and I adored it. I grew into my identity and became even more serious about pursuing a career in musical theatre. I still credit my time in performing arts with the development of my work ethic.

At age 18, I began to train at one of the top drama schools in London. Things were looking up.

But moving to a busy and complicated city without knowing anyone made me feel lost (both metaphorically and literally sometimes!).

I struggled to adapt. I struggled to make new friends. I struggled to understand abstract instructions like: “Dig deep into your diaphragm when you’re speaking.”

I seemed to get by for the first half of the term, but a hospital admission meant that I had to drop out of the course. Part of me was devastated; a bigger part of me was relieved. I had been so unhappy for such a long time.

Due to my experience of being in therapy, I started to consider a career in mental health services. However, with a BTEC in Performing Arts under my belt, I had to work my way up.

I started as an apprentice in a general hospital working with people with dementia and brain injuries – sitting with them to keep them safe during their stay, but also talking with them.

I loved it, but I felt out of my depth. My social skills weren’t the best, and I had to learn how to build relationships from scratch.

An older lady with dementia who I was working with was distressed for a long time. I felt helpless, but I discovered she loved Judy Garland from her hospital passport. So, I began to sing Somewhere Over the Rainbow, and she settled.

I was shocked but relieved to have brought her some comfort. I spent the next 12 hours singing that song on repeat. That was the very beginning of my journey to understanding how to support people on a human level.

By the end of my time in that role, I felt much more confident. The experience served me well when I moved into my first healthcare assistant role in a psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU) and when picking up shifts across adult mental health wards.

This is where I began to consider a career in psychology more seriously.

I was left in awe watching the psychologists at work. I loved how they thought, how they made sense of peoples’ experiences and worked with the team to understand how we could best support a client.

After a year in a peer support worker role, I applied for my undergraduate degree. I studied BSc Psychology with Clinical Psychology at Teesside University. I started in 2019, meaning most of my degree was suddenly shifted online due to the pandemic.

Oddly, I found that to be the best thing for me. Aside from the obvious costs related to the pandemic (we had many family bereavements ourselves), I valued the sheer hours I could spend on my new interest due to the lockdowns. I didn’t want to do anything but psychology-related activities.

I ended up taking on extra research assistant roles and volunteered to vaccinate people, so I never felt socially disconnected. I managed to gain so much experience during my degree.

Aside from this, I also had a specific learning difficulties assessment through university and was advised to seek an autism and ADHD assessment following this. My degree offered opportunities to learn more about autism, and I was pretty certain what the diagnosis would be by the time graduation rolled around.

I worked as an assistant psychologist for the next year and sat on an NHS waiting list for an autism assessment. At that time, they warned that the wait could be up to five years.

So, when I received an offer of a place on the doctorate in Clinical Psychology at Teesside University, I decided to opt for a private assessment. I thought this would help me secure the reasonable adjustments I may need.

One of the reasons I continue to study at Teesside is the amazing support it offers around accommodations and adjustments. It’s a really accepting place to be.

In July 2023, at the age of 26, I received my autism diagnosis.

What followed was a lot of reflection on my life experiences. I recognised that I was never wrong, broken or mentally ill; I just had a brain that worked a little differently. After a lifetime of self-criticism, I’m learning to be more compassionate to myself, but that’s a work in progress.

Many challenges come along with being autistic and working within a psychological profession. I know that close to my time of diagnosis, I really wished that there were lived experience accounts out there. I needed a sense of belonging in my career and to know how others were navigating their experience.

Since I couldn’t find what I was looking for, I decided to create it.

A month later, I teamed up with Dr Vicky Jervis, a consultant psychologist within Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust, and Dr Marianne Trent, a psychologist in private practice, and we started the search for autistic mental health professionals to contribute to our book.

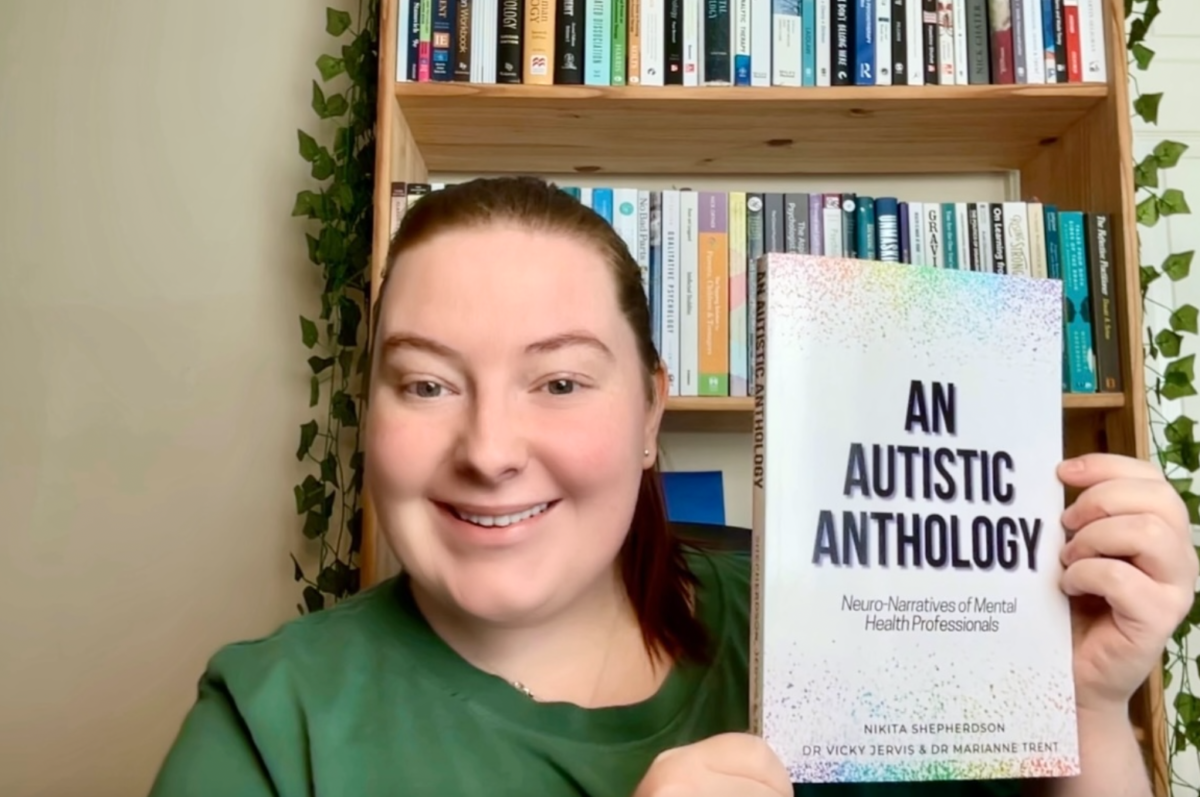

We recently published the work – An Autistic Anthology: Neuro-Narratives of Mental Health Professionals. It features 25 chapters, each written by a different autistic mental health professional.

We have representation from every region of the UK, as well as international contributors. A 12-hour flight from London would be the trip you’d need to take to reach the contributor who lives furthest away.

In the book, there’s a real sense of support and celebration for autistic professionals. At the time of writing, we are ranked as the #1 bestseller on Amazon in the Social Sciences category.

Improving visibility was always at the heart of this project, and, for the first time, we have a collection of professional autistic voices speaking out about their experiences.

Putting this book together has helped me to navigate my own professional experience, but it is an ongoing process.

I’m currently taking a break from my career and studies. Pressing pause is something I have never let myself do before, but I’m focusing on recovering from autistic burnout. I’m just learning more about what my needs are, listening to my mind and body, and responding to it.

The pathway to qualification as a clinical psychologist looks different for everyone, and I’m grateful that Teesside University continues to support me on this journey.

I will reach my destination in my own way – differently.

For information about autism, visit the National Autistic Society website.

If you’re a Teesside University student, you can learn more about the mental health and autism support available here. To discuss this further with one of our specialist advisers, book an appointment by emailing the Student Life team.