When my twelve year old called me a nerd recently, I pointed out that ‘nerd’ pays the bills. And then pointed out that he was an even bigger nerd than I was. And then we laughed, high-fived and went to do our respective homework because that’s how we roll. Clearly, he’s not wrong. And gaming is where he usually points this out to me.

The resurgence of Dungeons and Dragons, the fact that Warhammer is now worth over £1 billion, and that tabletop gaming generally is becoming more visible shows that the desire to play games is as strong now as ever. Games and gaming have been part of our collective history for thousands of years. The wonderful gaming piece found recently at Lindisfarne reminding us that even the Vikings took time out of all that raping and pillaging to pop open the Pringles and crack out the board games. Indeed, in their recent paper Hall and Forsyth argue that the introduction of games was an important aspect of cultural transmission in the Roman period.

And so I have followed in their footsteps. As a growing boy in my bedroom on my own, I did what you’d expect. Read through the Choose Your Own Adventure and the Fighting Fantasy books. And as I did my GCSEs and A-levels, my friends and I started playing games heavily. AD&D was our gateway drug, and we went on to play everything from Werewolf: The Apocalypse to Warhammer to Blood Bowl. Now that I think of it, in so many ways I’m academia’s Joe Manganiello.

My own forays into actual DMing started with the old Star Wars RPG (second edition, to be precise). Tapping into our collective love of the original trilogy, I created adventures full of rogues, droids and he-damn-well-shot-first moments. As much as being in the game was fun, I found it so much more exciting to devise the world and think quickly on my feet as my friends played through. You can plan all you want, but it all goes to shit when the characters pick an unplanned bar fight in a desert cantina and you need to figure out the stats and what to roll when they want to do the whole ‘why are you slapping yourself’ routine on an impoverished scavenger as happened more recently when using the Star Wars The Force Awakens set.

As a DM, you have to plan the time, set realistic goals, pace activities, maintain the interest of different people and be ready for unexpected questions. Which is basically every teaching session ever. Cultural anthropologist Holly Walters makes similar points, but extends the D&D analogy by examining student-player archetypes:

“For me, I simply never stopped being a Dungeon Master. I just eventually added a few degrees and a better title to it … In the end, I have to credit D&D as the thing that started me on the path of new pedagogy.”

In fact, when I was younger I wanted to be a teacher. Which I’ve sort-of ended up doing. My own teacher even noted that I was starting to show great leadership qualities. I’ll let you decide whether or not they developed successfully. I like to think that it was these that led me to play Jesus several times in school productions. If I’m honest, I don’t think I’ve ever really shaken off that feeling of being mankind’s saviour…

Of course you have to remember that playing D&D and Warhammer back then wasn’t as socially acceptable as it is now. Walking to school everyday to be punched in the head by the local bully wasn’t fun. But using those aforementioned fledgling leadership skills, I didn’t retaliate. Rather I let it go. For thirty years until I could write something snarky online. Actually, I can’t even remember his name and frankly these regular events are not even in the Top Ten of my childhood emotional traumas that comprise my Origin Story…

What I loved about those games, as well as the video games I tend to play now, is the freedom of choice. That sense of starting here and ending there, but that the way you get from start to finish is up to you. It’s really applicable to HE because it’s my experience that students perform better when they are doing things they enjoy the way they enjoy. I’ve tried to bring that ethos into my sessions and modules many times, although sometimes without enough due consideration. I know I’m very comfortable when someone says “Do what you want” but I haven’t been perhaps as conscious that others (students and staff) need a bit more structure when it comes to doing the activities I want them to do. It’s something I’m trying harder to keep in mind.

My most recent attempt to bring freedom of choice into the classroom has literally been through CYOA. I can’t remember where I first saw Twine, but it was over a year ago and it stuck with me. Here is a free online software which lets you create stories with many potential outcomes. Then it popped into my head again while I was trying to think of how to make a three hour session on forensic botany interesting. Yes, that’s right, I said it – forensic botany is boring. We tried it and you can read about our evaluation here in Forensic Science International: Synergy. An open access paper in the spirit of the open access software. TL:DR the use of non-linear stories improved student understanding.

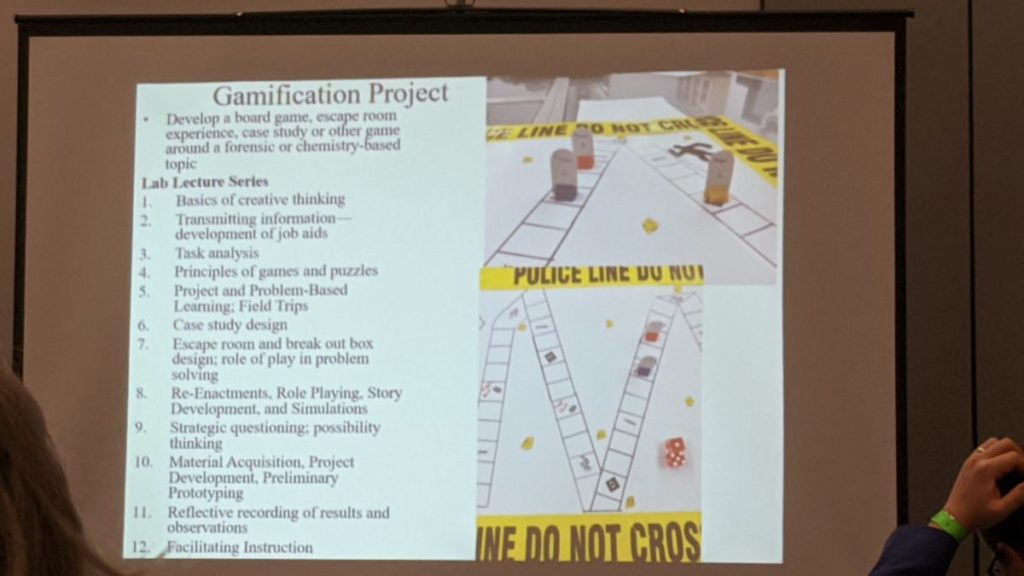

Which in a very long and unnecessarily convoluted way, brings us to the thing that got me thinking about all this. I’m at the American Academy of Forensic Sciences annual conference this week, and my first activity is a day-long workshop on learning and teaching in the forensic sciences supported by the Council of Forensic Science Educators.

They’ve called it High Impact Practices, but even after a full day of talks I’m slightly at a loss as to what is High Impact about it all. There is an official definition, which the Association of American Colleges and Universities defines as

“… practices that educational research suggests increase the rates of student retention and student engagement”.

Active learning, to you and me then. Although the talks were mostly very interesting, there wasn’t too much presented that we aren’t already doing at Teesside, or in most UK universities. What was notable was the lack of discussion of things like digital literacy. Towards the end of the day my heart leapt at the mention of gamification. But then my heart promptly un-leapt when the speaker dismissed it as anything other than making a simple game in class.

That sense of freedom and flexible learning styles was no-where to be seen, although it was present in other talks even if this wasn’t explicitly stated as such. For me, this was a bit of a missed opportunity to engage with an increasingly visible theme in learning and teaching. For all of the case studies highlighted today, student choice wasn’t really an intrinsic factor. The decisions on what teaching was done were all a bit top-down. But I can’t really complain – the session organisers simply chose their own workshop adventure…