Wow – I am poor at keeping these posts updated. I can only assume that you are all hitting the refresh button every week only to be crushingly disappointed that nothing new appears. I can only apologise and point to how very busy I am. Case in point, this weekend I was both appointed as the new President of the Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences and invited to give a talk at the 3rd International 19th National Forensic Sciences Congress in Turkey on forensic science education in the UK. I’m pretty sure no-one wants to hear about the former, but you might just be interested to know a little more about what I discussed with the delegates in Turkey. If not, well, I really can’t help you.

The talk covered some HE and legal context about the United Kingdom and then discussed the development of forensic science degrees. This is a well-trodden path, particularly by myself if I’m honest, so I’m not going to go over it again here. Other than to say (yes, yes, I know what I said…) that there was a huge influx of new degrees in forensic science, forensic chemistry and biology and the like as a result of a serious threat to the future of departments of biology and chemistry in UK universities. Can I call it an existential crisis? Maybe not, but it was bad. The huge interest in forensic science from a plethora of TV shows provided universities with an opportunity to attract new numbers and save departments and jobs. Yes, there were questions of quality, but I have addressed these issues elsewhere and I’m definitely not going to rehearse them here. Other than to say (I know, I know) that many of these complaints stemmed from a snobbishness of the subject, ignored existing HE quality assurance measures and removed student agency from the process.

One area which I haven’t touched upon before (I heard that sigh of relief…) is the impact that pulling forensic science education into universities has had on the wider discipline. I’d argue that situating any discipline into HE is of benefit to that discipline and those who work in it (the same can be said for nursing, paramedic practice, policing and so on). Specifically here, I’d argue strongly that because forensic science education is now based in universities, we have seen:

- an increase in research activity

- improved staff quality overall (both from an increase in doctorally qualified staff and the transition of staff from practice into HE to teach the next generation of practitioners via formal pedagogical frameworks)

- an improvement in the understanding of the science which underpins our forensic disciplines, plus an expansion of that understanding

- increased interdisciplinary collaboration

- widened access to forensic science for the public (e.g.: Innocence projects and cold case reviews) and students

Whilst acknowledging all of this, we still need to grapple with the issue of quality in the teaching of forensic science – or at least the perception of quality. As I noted in my talk, the UK higher education system is well regulated, and we have a variety of metrics that are used to assess quality. These are often then brought together to create league tables of various persuasion.

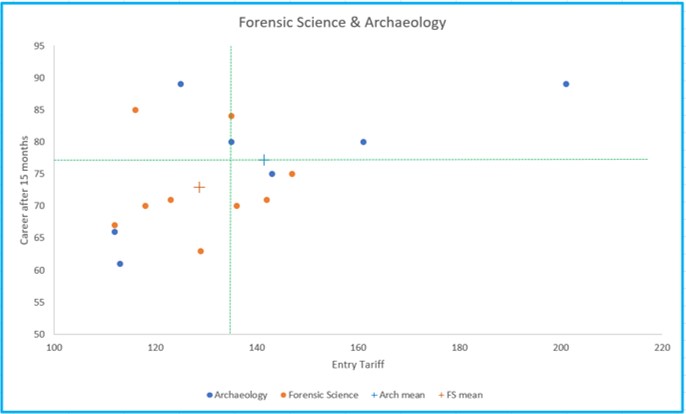

One of the problems when league tables are constructed from different data sets, is that the results can be confusing or lack context. Let me give a couple of examples. The graph below I’ve used before – albeit when talking about graduate jobs. This time, I’ll use it to make a different point (thus cleverly avoiding the whole self-plagiarising thing…).

The tension we see here is between metrics used to measure quality by entry standards and our social mobility schemes. Entry tariffs are used in league tables (the higher the tariff, the higher the league table position) but these are usually achieved at the expense of widening participation missions. Thus universities with strong widening participation and an emphasis on social mobility tend to feature lower on league tables. The lower rates of graduate employment shown here are not a function of quality of provision but rather the challenges faced by geography and social capital.

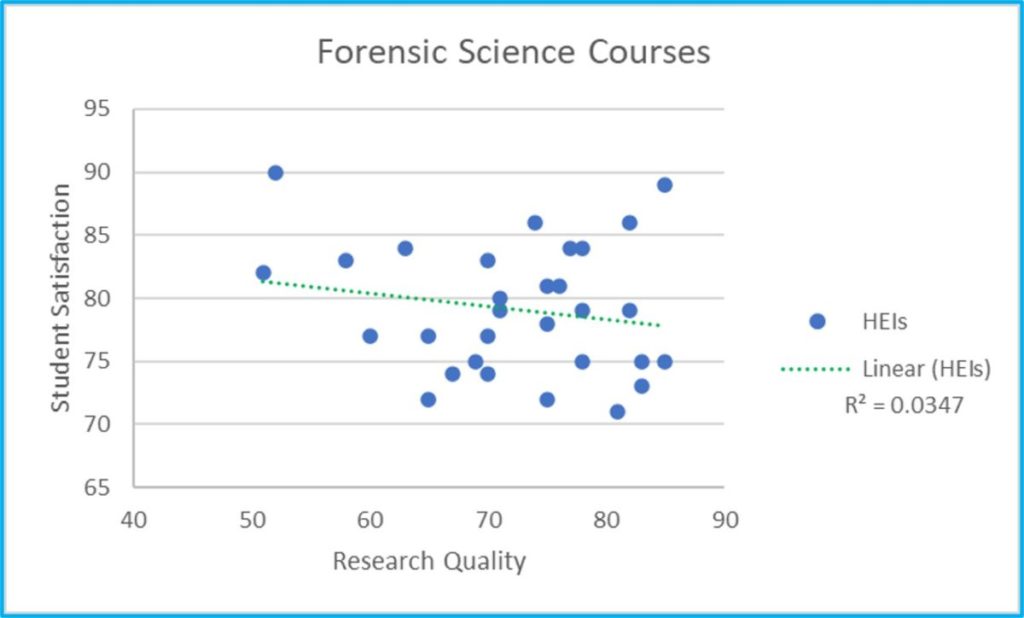

Another example. This time with a line of best fit! Because – science! Do we define degree quality based on teaching or research? Because as you can see from this data collated from the Complete University Guide, the two are, on the whole, at odds with each other. Although I recognise that I am using ‘line of best fit’ here in it’s absolutely loosest sense.

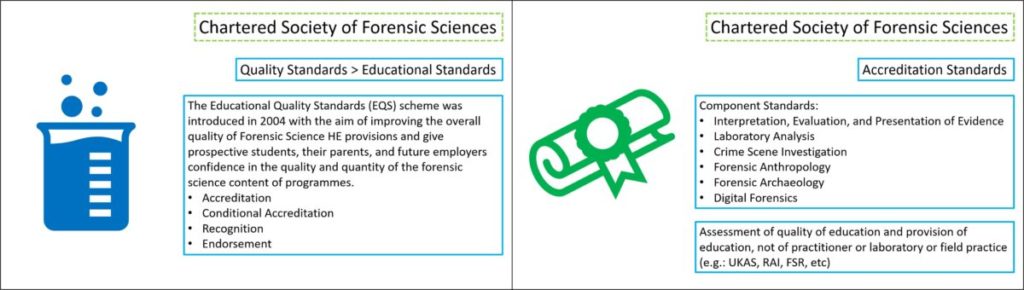

Of course, league tables are just one way of determining quality. Another way is through a form of peer assessment, which is the basis of the Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences’ (CSFS) approach. Here fellow experts in forensic science education and practice review degree courses with a view to awarding accreditation (or one of the newer levels below this which recognise elements of forensic science provision). We now have six component standards (see slides below) which are used in the UK but also in other countries too, and each standard reviews an aspect of the degree course.

It’s important to note here that the CSFS does not accredit practitioners (discipline accreditation can be achieved through other professional bodies, or pedagogical accreditation through Advance HE) or laboratories and processes (which are assessed via UKAS and ISO standards).

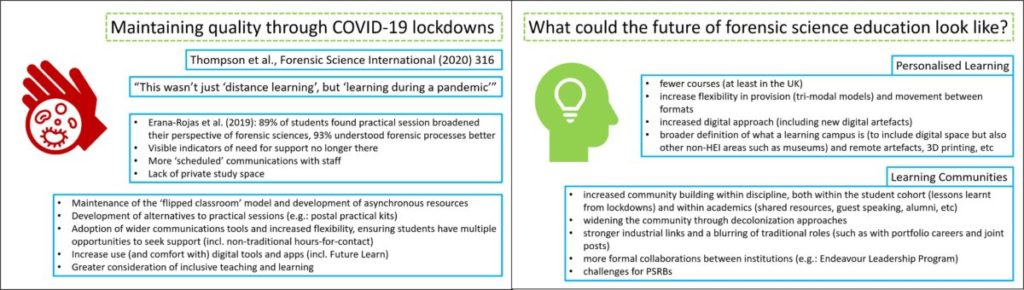

So, what of the future then? First of all, I presented some developments from the COVID lockdowns that I thought would and should be carried on. You can have a look at the slide below to see what I said, I’m not typing everything out for you, I have things to do.

Then I double-downed on the two areas that I think will see the most significant pedagogical developments in forensic science – the evolution of more flexible, personalised learning opportunities, and the expansion of learning communities, particularly across HE institutions. The former could be tricky since it aligns with student expectations, but the latter could really improve the quality of the provision itself, allowing a greater variety of expertise to be brought together for the benefit of our students. I think this will also help less-well resourced institutions to contribute to our agenda. This is not to say that these will not bring challenges, for example for Professional, Statutory and Regulatory Bodies (PSRBs) that may want to accredit courses that vary in greatly in style, mode and are pan-national (I’ll be honest, not ideal as I now lead one such PSRB) but how exciting will it be to engage in these developments.

For me, forensic science education has been showing increasing maturity, something which has been intensified as we worked through lockdowns and isolations. I genuinely think that this is the most exciting time for forensic science education. Surely only a coincidence then, that it coincides with me moving out of the classroom somewhat…