The problem with having friends is that they invariably ask you to do things for them, and you can’t say no. This is one of the reasons why I generally try to avoid social connections – although I undermine my own principle here by being an absolute delight to be around… It was just such a request that took me to the docks in London…

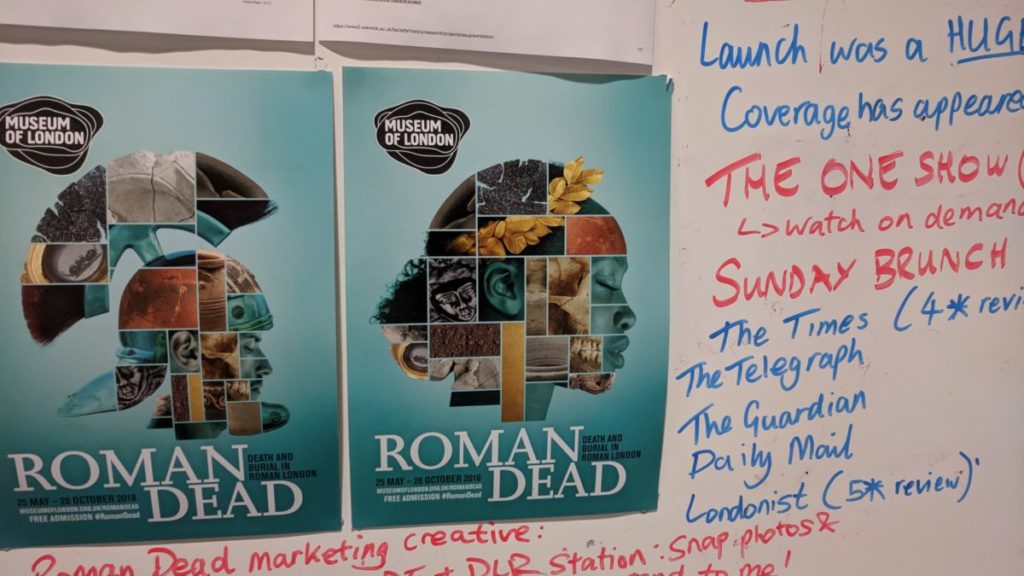

I’ve said before how much I enjoy visiting the Museum of London, and more so because I am good friends with two of the curators of human remains down there. They’ve been working incredibly hard recently pulling together the new Roman Dead exhibition, which is now open at the Docklands building. The building itself is lovely and reminded me of the International Slavery Museum I visited recently, in that it’s an old dockside warehouse which has been converted for modern uses. You even have to use the Docklands Light Railway to get there, which is always brings out the child in me because it travels without a driver!

Anyway, you may be aware of this exhibition already since it caused quite a bit of controversy when it opened. Not real controversy obviously, but rather that media controversy that can develop when a perceived sense of history is challenged. There have been a number of scuffles recently when academics have pointed out that Roman London was probably quite diverse:

- Mary Beard abused on Twitter over Roman Britain’s ethnic diversity

- If Mary Beard is right, what’s happened to the DNA of Africans from Roman Britain?

This has been shown from the materials recovered from the city, but also from analysis of the stable isotopes within the skeletons of the deceased. This latter form of evidence is particular useful for highlighting diet and migration in the past, such as in Shaw et al’s 2016 paper ‘Identifying migrants in Roman London using lead and strontium stable isotopes’. But for some, this is all too provocative and an example of ‘elite’ academics smearing the past with modern-day liberal sensibilities. A nonsense, of course, and even my limited understanding of Roman society tells me that this was a society whose success was partly due to its ability to incorporate diverse peoples and cultures.

The exhibition itself features a number of examples of cremated and buried individuals, with accompanying details of what these remains tell us of the past. There are also a number of artefacts associated with the funerary processes of the time. The Times felt that the exhibition:

“does a good job of bringing together the visible and invisible to tell the tales of London’s Roman bones”.

As part of this exhibition, the Museum had organised an evening of talks on aspects of the Roman Dead. Dr Valerie Hope kicked things off with an interesting discussion of Roman funerary practices and the flexibility of the rites used in the build-up to the cremation or burial. This was followed by Dr John Pearce who invited us to imagine how someone from the time would have seen and interpreted the funerary monuments outside of London. I was the final speaker, and discussed the physical effects of cremation on the body and how we can use these heat-induced changes to interpret funerary practice.

One of my examples was our work on the cremated remains from a number of military sites along the northern frontier. Here we were able to show the similarity of the burning processes in these different locations despite the variations of goods buried with the bodies. We’ve interpreted this as evidence of dual identities in these individuals – one derived from being in the military (the burning) and one associated with their individual histories (the artefacts).

Th exhibition has been incredibly successful. Over 6000 people have visited it already, and it will be open all over the summer.