“The story of transatlantic slavery is a fundamental and tragic human story that must be told and retold, and never be forgotten.”

I’ve been desperate to visit the International Slavery Museum for ages. I’m currently an external examiner for the forensic anthropology undergrad and postgrad degrees at Liverpool John Moores University and so come over to the city a couple of times a year. I really like Liverpool – partly, as I’ve said before, I like post-industrial cities that look both to the past and to the future while retaining a real strong sense of self. I also put Manchester, Sheffield and Dundee in that category. Anyway, I’ve been working my way around the various cultural highlights over the years, but have never managed to get to this one. The museum is situated down on the docks, and is part of the Merseyside Maritime Museum.

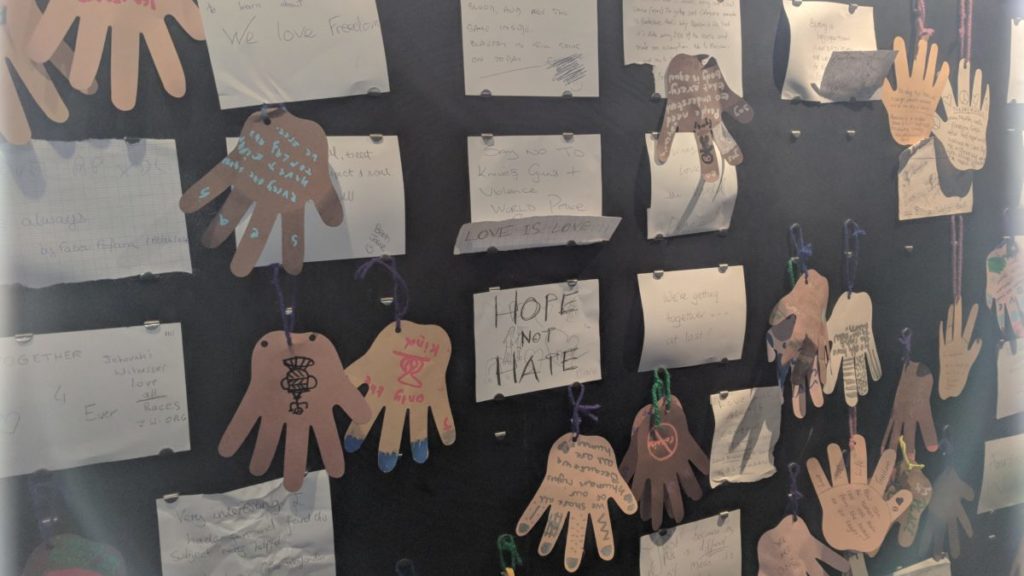

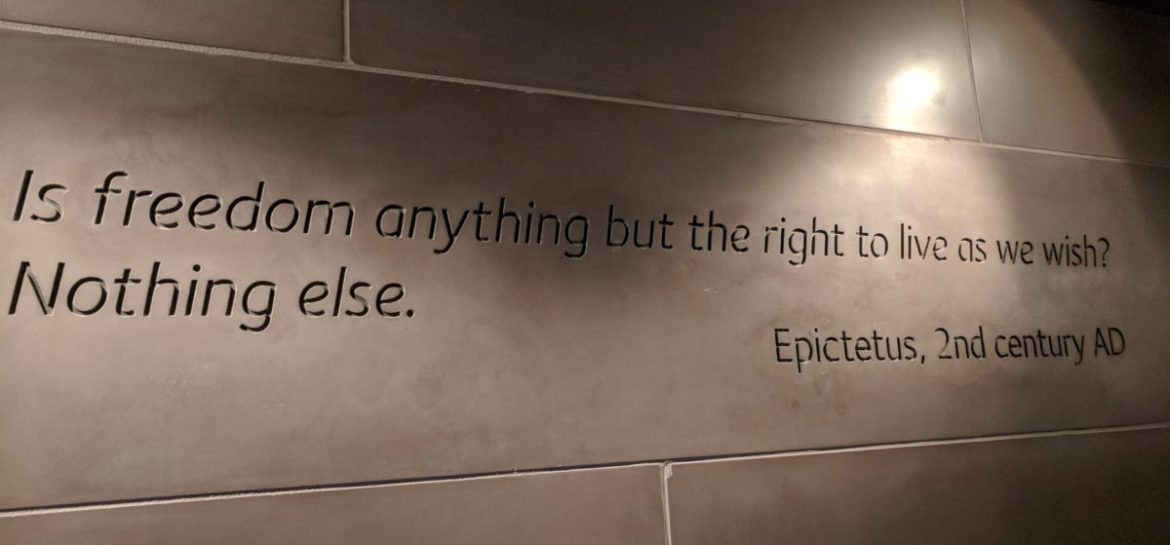

The museum isn’t huge, but takes you through three stages – the African lives pre-capture, the middle voyage, and then the legacy of the slave trade. It’s a fascinating exhibition – although it is filled with horrors and is yet another example of the British being, well, just the worst. Dotted around the museum are artefacts from this period – including bills of sale. If you watch the excellent Who Do You Think You Are? and marvel at the volume and quality of paper records that have survived the years and the meticulous detail in which records were kept, you will know what to expect here. One of the things that I hadn’t appreciated is that the start of the transatlantic slave trade moved goods to the west African coast and then people over to South America such as Brazil. The early work of the slaves was to recover precious metals and resources (rather than sugar or tropical goods) – largely, as was noted from records of the time, because there were not enough of the local population to use as slaves because the European invaders and slaughtered everyone. Seemingly in Britain, for every “we invented the internet” there’s a “yes, but here’s another crime against humanity”. Sigh. Anyway, it was only later during the slave trade that the slaves were brought to the Caribbean and into North America. But nonetheless, the trend was the same – goods down to the west African coast, trading of goods for peoples’ lives, forced movement of people across the sea to Brazil, Peru, Mexico, Jamaica, the US and so on.

As you well know, my main work is on the human body and so I’m very interested in the physical impact of slavery and forced migration. In our book (you know, the one from that review…), we talk a bit about the long-term physical effects of slavery and the impact that it has on descendants of slavery. Researchers have noted how gene expression has been influenced by the effect of the transatlantic slave trade. If you don’t fancy reading the discussion of it in our book, you could pop along to Teen Vogue to read a summary from 2016 there, where they note that:

“Sociologist Dr. Joy DeGruy played off the widely accepted term Post Traumatic Stress Disorder to create the phrase Post Traumatic Slave Disorder to address the specific trauma suffered by descendants of black slaves.”

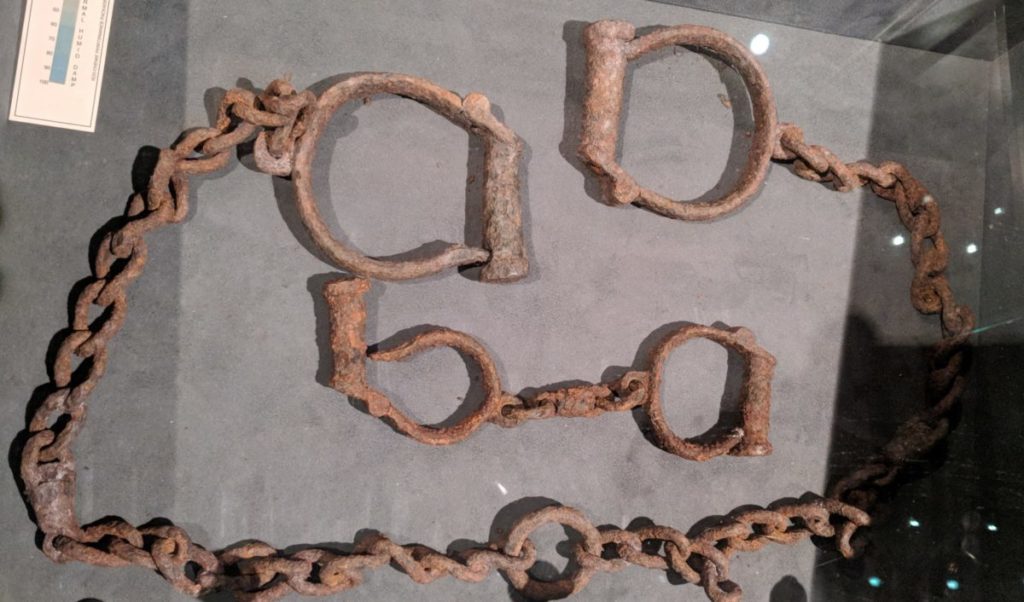

The museum also reminds us of the more immediate physical trauma that was caused to these victims. There are a number of images displaying the torture that was used to coerce the slaves, but also a video reconstruction of a mother describing watching her son being chased down and beaten. There are also some artefacts on display, including the manacles below which were used to chain people as part of a punishment.

I run a final year bioarchaeology / anthropology session at Teesside which focuses on migration, and we use the transatlantic slave trade as an example. I like to draw on some of the published isotopic work (such as Schroeder et al’s study from Barbados in AJPA) or the recent genetic studies (like the one by Moreno-Estrada et al in PLoS Genetics titled ‘Reconstructing the population genetic history of the Caribbean’ – which is also open access). There are others, I know, but these ones are easily accessible for students who are new to the topic, as mine tend to be.

So why is this museum in Liverpool? Well, the city has a long, somewhat shameful history with the slave trade. As the display in the museum states:

“By the 1780s Liverpool was the European capital of the transatlantic slave trade. Liverpool was responsible for transporting nearly 1.5 million Africans into slavery – more than 10% of all known Africans transported.”

Indeed, so closely linked with the slave trade was the city, that ships for the Confederacy were made here during the US Civil War.

Eaves-dropping on the museum guide for the tour group behind me, I noticed that the guide ended by stating that there are more people in slavery today than there were back when the transatlantic slave trade was thriving. Although it really shouldn’t have to be spelled out, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation state:

“While the means through which modern and traditional forms of slavery have operated differ greatly, the violation of human rights and human dignity are central issues in both practices, such as proclaimed in the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

A sobering end to a thought-provoking museum. You can read more on the modern-day slave trade here in a dedicated section of the Guardian or at the UNESCO pages.