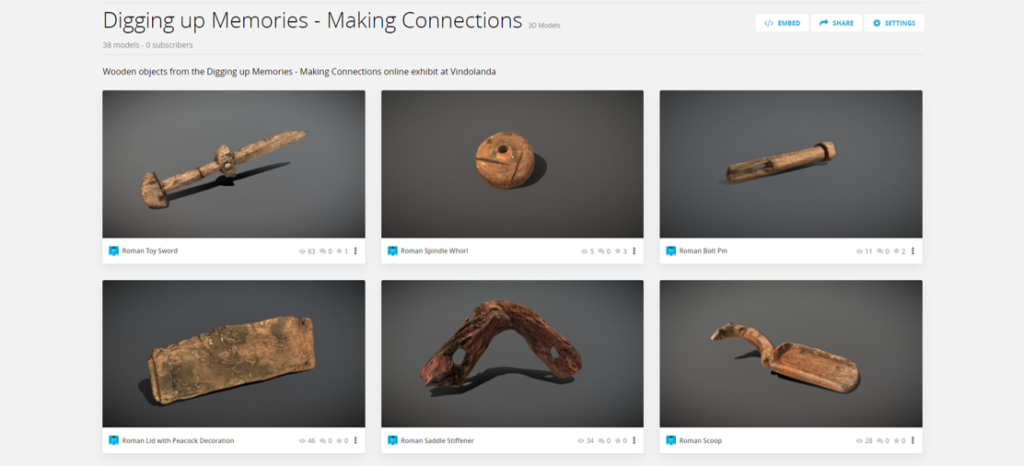

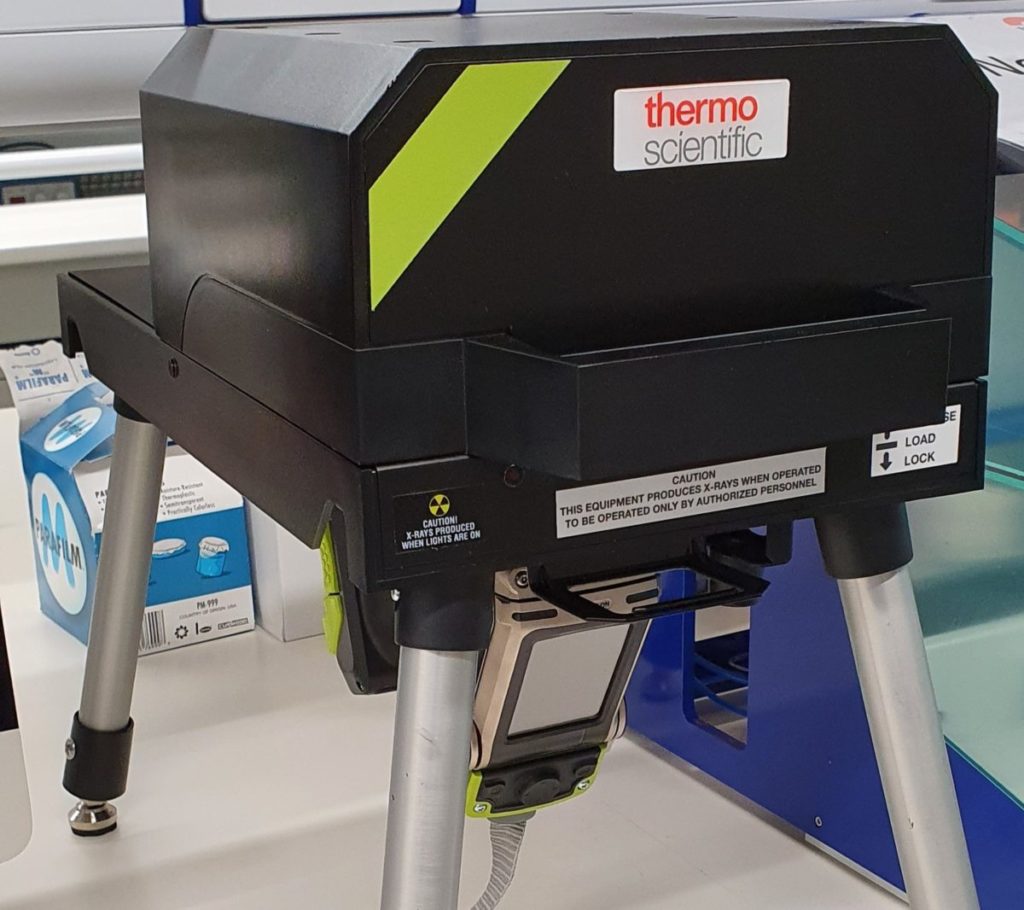

You may remember a previous blog post when we set out 3D scanning a whole range of different wooden artefacts for the Digging up Memories – Making Connections online exhibit with Vindolanda Museum. Well here we are, looking back at all the successes and improvements after the exhibit was released to the world! We’ve recently written about online exhibits in the book Hadrian’s Wall: Exploring Its Past to Protect Its Future, but here we’re going to review through our recently published paper on the Digging up Memories exhibit.

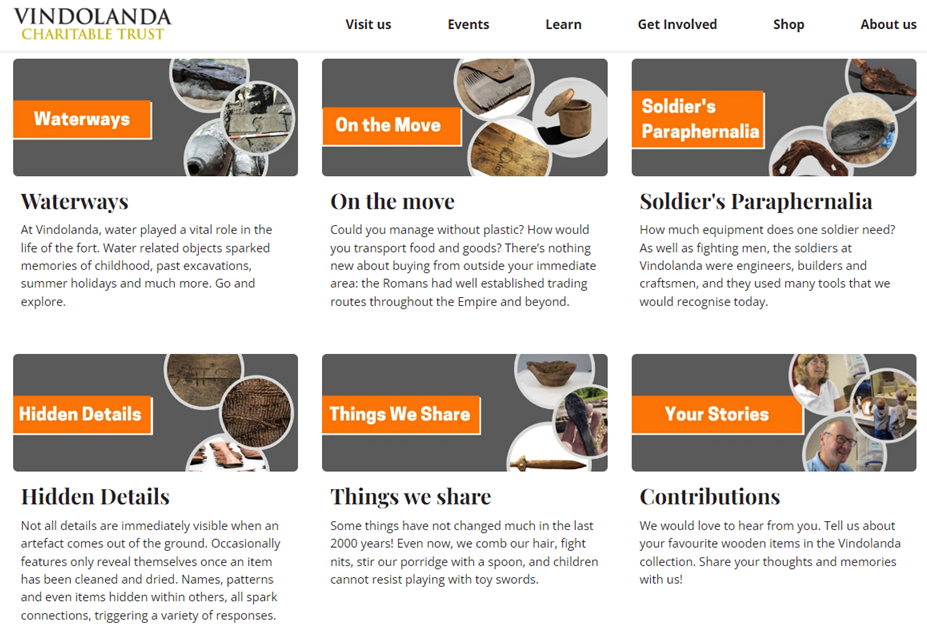

This exhibit focused on the precious objects that comprise the Wooden Underworld collection at Vindolanda. Objects were selected by museum workers, volunteers and contributors to ensure co-curation in the exhibit, branching the breadth of roles at Vindolanda Museum. The exhibit was held on the Vindolanda website to help ongoing public engagement during limited visitation times and beyond, still remaining accessible today.

Our early priority was multimedia excitement. Yes that sounds like a bit of a buzzy phrase but essentially, we want several types of media to engage the different preferences and interests of our audience. This meant not just 3D models but also photos, sound bites, video interviews, voice recordings of contributors, lectures, creative writing, published reports, all sorts! Clearly this had some attentive impact, achieving an average 1 minute 35 seconds spent viewing per page (compared to the “typical” museum exhibit times of half a minute).

Now you may be wondering, which objects were the most popular? First, why not take a look at the exhibit yourself and pick out which one is your favourite!

Had a look? Great! The Things We Share page was the most visited, with the Toy Sword achieving the most views overall. Personally, we love the toy sword – Rhys even gave an interview about it in the exhibit!

A key question was “so… was it worthwhile?”. Yes! We had so much valuable feedback but the most valuable measure for us was that 88% of respondents felt encouraged to look further into Vindolanda and Roman history. Now that is a clear success for museums hosting online exhibits! If you’re interested in setting up your own online exhibit, check out the publication which goes into more detail, and offers suggestions and recommendations for future projects.

Isn’t technology great?