Replica worlds – the education benefits of bloody violence in the grimy streets of physical and virtual reconstructions of the past

Categories Learning & Teaching

Let’s face it, children are idiots. They whine a lot and rarely know what’s good for them. For example, some of them don’t even realise that a trip to a museum is not a chore. It’s fun! Who doesn’t want to learn things?! Idiots, that’s who… Anyway, it was just this attitude that we were faced with on a recent trip to Preston Park.

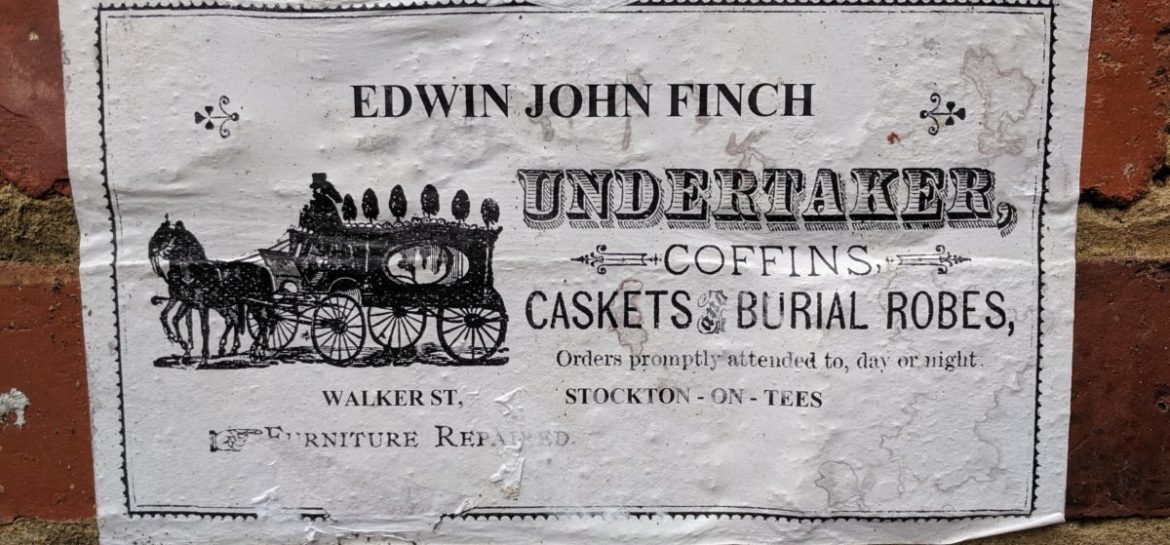

Preston Park is a museum and gardens complex near Stockton. The large house was built in 1825 and became a museum in 1953. The museum is nice enough and focuses on the local area (evidence of human activity in this neck of the woods can be traced back to the Mesolithic) but the best thing here is the replica Victorian street. This meticulous reconstruction features a number of shops and services, and there’s even a cafe, although I’m not sure how Victorian my latte was… Anyway, it’s a wonderful immersive experience where you can dress up as street urchins.

But not for everyone was as excited as I was…

So how to get these idiot children to enjoy the visit, and I don’t know, maybe even learn something along the way. Well, it just so happens that we’ve been playing a game called Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate. Based in Victorian London, the game allows you to run around the streets and rooftops of a reasonably historically accurate London while chatting to the Queen, protecting Charles Darwin’s publications, ghost-hunting with Dickens and stabbing ne’er do wells in the throat. The last point is less pertinent here, to be honest…

There’s still a tangible snobbery about bringing video games into higher education, despite the fact that the games industry has now surpassed film and music as the most profitable entertainment industry and that HE has a huge impact in creating and supporting this industry through our work in producing talented graduates and backing start-ups. Recent press has also underlined the significance of the digital sector to the economy of the north-east. Part of the issue, I think, is that it is still viewed as trivial and atheoretical- which again is not necessarily true and is also an argument which fails to acknowledge just how many TV shows, films and (dare-I-say-it) books are crap.

There’s even a growing body of work underlining the potential of using games in learning. I don’t mean gamification per se (that is, using game theory to enhance learning) but rather that the games themselves offer an opportunity to, say, experience the past in novel ways. The creators of Assassins Creed have recognised this themselves, with the inclusion of an education mode in their recent release set in Ancient Egypt. To be honest, even the non-educational stabby-stabby versions of the game have a database of historical figures and locations that you populate as you progress through the game. And stepping away from historical contexts, initiatives like Games for Change provide new and interactive ways to understand contexts as broad as the refugee experience (in Against All Odds, by the UNHCR), rainforest ecosystems (in Tree, by New Reality Company), the challenges of LGBTQ youth (in A Closed World, by Singapore-MIT Gambit Game Lab) and living with autism (in Auti-Sim, by Taylan Kadayifcioglu, Matt Marshall and Krista Howarth). Used cleverly, these games allow educators to approach a range of subjects from less didactic standpoints. As Matthew Farber notes in Gamify your Classroom, “Games empower people – often more so than real life can … students project themselves onto characters. The teacher must ‘unpack’ these experiences” (2015; 227).

For our ungrateful children, being able to see and walk around the Victorian street and it’s shops mirrored what they had done in the game. It allowed us to transfer our experiences from one context to another, and to get some reluctant children to engage with the past a bit more. We could, for example, talk a bit about how difficult life was for children working in the factories because they had just saved some from this fate in the game; or about the challenges with unsanitary conditions because we saw a water pump in the museum and in the game you have to stop an outbreak of poisoning. Both the game and the street were replicas of the past but could offer different approaches to interaction with that reconstruction of the past. And thankfully most of this was possible without having to stab anyone in the throat…