Written by

Dr Paul Sander, Lecturer in Psychology at Teesside University; email:P.Sander@tees.ac.uk

About 20 years ago two important things came together. The first was the publication of a paper and the second was the arrival of an email. The paper shared research on student expectations which showed that students in high and low tariff universities had different expectations. We wondered whether this could be explained by different levels of confidence in their study behaviour, leading to the development of an Academic Behavioural Confidence scale (ABC). In a succession of exploratory papers, we considered the factorial structure of the scale, translated it into Spanish, pursued structural equation modeling and with Dave Putwain, then at Edge Hill University and now at Liverpool St John Moores University explored how confidence changes over time and how it might correlate with outcome grades.

The other event from those early years of this century happened one dark, wet, December day, when, putting off cycling home, I heard my email ping. It was a message that clearly had gone to all psychology departments in the country. It was from hot Spain, so I eagerly replied, opening a conversation about Erasmus exchanges, an EU funded scheme that allowed students to study for a semester or a year in another EU member country, taking their grades back to their institution. When I eventually went there, Jesús de la Fuente introduced himself and with time, he became a research collaborator and a friend which led almost immediately to student mobility between the University of Almería and Cardiff Metropolitan University.

In 2012 everything changed. I decided to have my second mid-life crisis[1] and run away to Mexico, never expecting to return. Despite my crisis Jesús and I stayed in contact, working on data and ideas which lead to me starting to write the paper that would become Modelling students’ academic confidence, personality and academic emotion, eventually published in July (2020). The journey to that moment was one of the worst writing experiences. Peer reviewing is not generally kind and supportive to dyslexic authors. This time it was suggested that English may not be my native language. I accept that the paper was co-authored by a Spaniard and was based on data from Spanish undergraduate students but really, the audacity, if not the stupidity, of the suggestion still haunts me.

[1] the first was buying a car but that is another story.

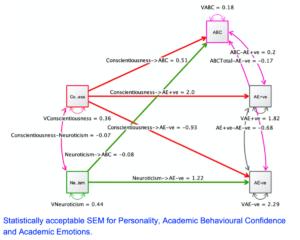

Data was collected from students via an online platform. The ABC scale was completed by 1398 students; the Big Five, which measures the personality traits of Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism, was completed by 636 and, for academic emotions, 551 students. Analysis showed that Neuroticism negatively correlated with ABC; Openness, Conscientiousness, andAgreeableness positively correlated with ABC. There were also strong correlations between the ABC sub-scales of Grades and Verbalising with the Big Five factor Conscientiousness. Further, ABC positively correlated with positive academic emotions and negatively with negative academic emotions and that Neuroticism negatively correlated with positive emotions and positively with negative ones. The Big Five traits of Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness and Openness positively correlated with positive academic emotions and negatively with negative academic emotions. Following our interest in using structural equation modelling, we built the model shown below, the final, reduced and most parsimonious, using Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, an aggregate ABC score and aggregate positive and aggregate negative academic emotions.

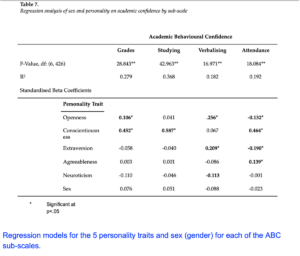

The second paper Undergraduate student gender, personality and academic confidence, with data collected via the same platform, explored an interest in gender differences in undergraduate student study attitude and behaviour (for example). Here, data from 469 male students and 1321 female students on ABC and Big Five Personality was collected. Female students were significantly more confident than male students on the ABC sub-scales of Grades, Studying and Attendance but less confident than the male students for Verbalising.  Female students scored significantly higher than male students for Conscientiousness, Neuroticism and Agreeableness. Also, Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion and Agreeableness positively correlated with the ABC sub-scales: Grades, Studying, Verbalising and Attendance. Conversely, Neuroticism significantly negatively correlated with each of Grades, Studying, Verbalising and Attendance. In the final regression models for each ABC factor (see the table below), gender is not significant as it was subsumed by Openness and Conscientiousness as the variables were incrementally added.

Female students scored significantly higher than male students for Conscientiousness, Neuroticism and Agreeableness. Also, Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion and Agreeableness positively correlated with the ABC sub-scales: Grades, Studying, Verbalising and Attendance. Conversely, Neuroticism significantly negatively correlated with each of Grades, Studying, Verbalising and Attendance. In the final regression models for each ABC factor (see the table below), gender is not significant as it was subsumed by Openness and Conscientiousness as the variables were incrementally added.

In line with previous research (Vedel, 2014), the personality trait, Conscientiousness comes out as the most dominant contributor to the Academic Behavioural Confidence measures. Academic Behavioural Confidence, arguably, is a useful construct because, in addition to the findings presented here, it has been found that: students with higher dyslexia scores have lower Academic Behavioural Confidence; It varies predictably between courses with different entry requirements and is higher in students with a deeper approach to learning and with higher grades. It also tends to decline during a course of study but most of all it has given me friendship and collaboration.