Written by

Blossom Bell, MSc Health Psychology, Research student at Teesside University, Centre of Applied Psychological Science; Email: b.bell@tees.ac.uk

Dr Katherine Swainston, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Centre for Applied Psychological Science, Health and Wellbeing theme; Email: k.swaintson@tees.ac.uk

In 2016, Blossom returned to academic study after a career within the shipping sector. Initially qualifying as a navigational officer within the merchant navy, she navigated tankers worldwide before achieving a BSc Hons in Nautical Science. Using her professional experience, she later spent a period of time lecturing new recruits before working for a shipping registry in central London. It was during her time in London that her interest in psychology and long-term late effects following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation began to flourish. Deciding to hang up her sea legs for good, Blossom returned to academia and completed an Introduction to Psychology course, followed by a Graduate Diploma in Psychology and then a Master’s in Health Psychology at Teesside University.

As her studies progressed, her research ideas focusing on post hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) monitoring services also developed. A HSCT is a procedure undertaken to treat conditions where blood cell formation has been damaged or compromised due to an inherited condition, as a result of cancer or as a consequence of cancer treatment. Blood cell formation occurs within the bone marrow and starts with haemopoietic stem cells (HSC), which self-divide. One half of the cell goes on to produce other blood cells while the remaining half stays as a stem cell to repopulate. Damage to HSC means that new healthy blood cells are unable to form and as a result a HSCT may be advised. A HSCT is the transplant of hemopoietic stem cells from sources such as bone marrow or peripheral blood either from a donor or previously collected from the patient’s own HSC, or from umbilical cord blood donations. The reintroduction of healthy HSC can repopulate the bone marrow to normal healthy status. While HSCT offers a cure from the underlying condition, recipients requires long-term monitoring post-transplant.

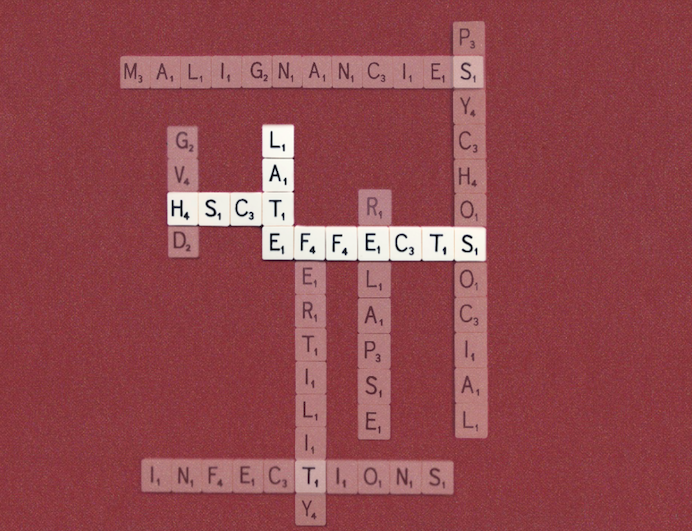

The establishment of dedicated transplant centres nationwide, as well as medical and technological advancements, have led to an increase in the number of HSCT’s being performed in the UK. While numbers have increased so have the known associated risks, referred to as late effects and include infection, relapse, organ dysfunction, and secondary cancers. There is a vast array of literature highlighting the mortality and morbidity risks post-transplant, and as a result, international guidelines for long-term monitoring were established. These provide guidance on screening and preventative services to identify late-effects and relapses early to optimise the outcome, reduce morbidity and mortality. Despite a considerable growth in research over the past two decades around late-effects, there is a lack of research examining late-effects from the recipient’s perspective. Keen to develop this area further Blossom, who is a transplant recipient herself, contacted Dr Katherine Swainston, who has experience working within this field, and so Blossom began researching HSCT late-effects for her Master’s in Health Psychology research project.

Blossom conducted a thematic analysis of a free-text questionnaire followed by two online interviews to explore the lived experiences of long-term monitoring for HSCT recipients in England. The study highlighted variation in recipients’ experiences of long-term monitoring services post-transplant, including different levels of monitoring intervals and logistical arrangements. Long-term monitoring was either organised directly through the transplant centre, as a dual approach between transplant centre and local primary health care trust, or local health care monitoring only. Main findings included a variation in recipient knowledge and awareness of late effects, problematic access to screening services, lack of coordination between transplant centre and primarily health care providers, and specialist knowledge of late effects from health care professionals at primary level. Furthermore, participants highlighted being apprehensive in relation to cancer recurrence and uncertain future health and expressed a need to further understand risks and how to reduce these.

The study findings demonstrate the complexity and importance of exploring HSCT recipients experiences further to deliver a patient-centred management service. Blossom has now registered to undertake a PhD at Teesside University within our Centre for Applied Psychological Science under the supervision of Dr Katherine Swainston. The research will begin by exploring how post HSCT monitoring and associated health threats impact recipients lived experiences. A qualitative approach will be undertaken utilising interviews and a life grid approach to ensure in-depth exploration of meaning and experience. On the basis of the PhD findings, strategies and interventions for supporting patients through increased awareness and health behaviour change interventions, where possible, will be identified and developed with the support of a patient and public involvement group.