On the surface level, these two species probably couldn’t be any more dissimilar. One a ferocious predator in the water, and the other as harmless as a common fly. But the way in which these two species reproduce bare interesting similarities, despite their stark visual differences.

Crocodylus acutus courtship is a seasonal event, that usually takes place in the first two months of the year. (Animal Diversity Web). The typical behaviours during this period are mostly territorial to compete for a mate and include: a number of head slaps (initiated by the female) which is often responded to with an extremely low frequency sound – “Sub Audible Vibration (SAV).” Garrick and Lang (1977). Though Animal Diversity Web also adds that these behaviours include a series of loud roars and an impressive display of their teeth.

Sexual maturity is often reached between 1.8m – 2.4m, or between 8 and 10 years old. (Although Alvarez del Toro (1974) and Varona (1980) never found a reproductive female under 2.7m.) Mating is polygynous and occurs between the months of April and May, resulting in a spawn of usually between 30 and 60 eggs (Though Schmidt (1924) found a litter size of 22 and Medem (1981) a litter size of 105 – Both state that these instances could have been results of predation, or multiple litters in the same location.) The eggs are laid into holes dug into the ground, often 1.5m-1.8m deep, where rotting vegetation is laid on top for warmth. (See figure 1) Figure 1 – an image of a Crocodylus acutus nest with eggs (Nature Picture Library, n.d.)

Figure 1 – an image of a Crocodylus acutus nest with eggs (Nature Picture Library, n.d.)

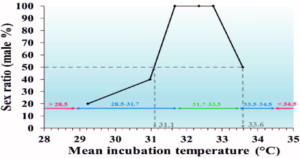

Crocodylus acutus has a total of 32 chromosomes and are diploid in nature. The sex of the offspring produced through sexual reproduction is based off the temperature of the eggs during the thermosensitive period of incubation, as Crocodylus acutus lack sex chromosomes. (National Library of Medicine) Temperatures below approximately 30°C and above 33°C produce females, whilst temperatures around 31.5°C produce males. (Research Gate, 2017) (See figure 2)

Figure 2 – Mean incubation temperature and the resulting sex of Crocodylus acutus‘ offspring. (ResearchGate, n.d.)

Figure 2 – Mean incubation temperature and the resulting sex of Crocodylus acutus‘ offspring. (ResearchGate, n.d.)

Like the Crocodylus acutus, the Quercus robur reproduces sexually, but on rare occasions can also reproduce asexually. This is known as parthenogenesis. Sexual reproduction requires the presence of another Quercus species to act as a pollen donor (International Oak Society, 2014). Quercus robur are also seasonal breeders, with fertilisation happening in the Spring and the seed maturing around October (The Conservation Volunteers, 2025). They produce around 2000 seeds, or acorns, each season – though this can vary drastically due to “masting” – one year every five where a single Quercus robur can produce in excess of 10000 acorns (Mass Audubon, 2023).

However, each tree possesses both male and female flowers (See figure 3), though they appear at different times in order to prevent self-fertilisation. However, in rare cases it has been found that some Quercus robur have self-pollinated. Male buds appear as long clusters, and appear between April and May, whereas female buds appear as red flowers that populate between the branches and leaves. (Woodland Trust, 2025). Furthermore, the Quercus robur only reach sexual maturity at 30-40 years old (Forestry England). As mentioned before, the Quercus robur can also reproduce asexually through a variety of means and processes, either naturally or artificially. Coppicing refers to when a tree is cut down, and the dormant buds that remain in the leftover stump or root collar sprout (Future Trees Trust, 2024) Layering can also occur when low branches that come into contact with the ground can grow into new trees.

Figure 3 – an image showing the difference between male and female flowers on a Quercus robur. (Season of Earth, n.d.)

Similar to the Crocodylus acutus, the Quercus robur’s chromosomes are diploid, and has a total of 24. They also lack any sex chromosomes as all Quercus robur have both male and female flowers – this is known as being monoecious. (Sax, 1930).

References

Álvarez del Toro, M. (1974) Los crocodylia de Mexico.

Animal Diversity Web (2009) Crocodylus acutus. Available at: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Crocodylus_acutus/ (Accessed: 5 November 2025).

Charruau, P., Cantón, D. and Méndez-de-la-Cruz, F. (2017) ‘Additional details on temperature-dependent sex determination in Crocodylus acutus’, Salamandra, 53, pp. 304–308.

Forestry England (n.d.) English Oak. Available at: https://www.forestryengland.uk/article/english-oak (Accessed: 5 November 2025).

Future Trees Trust (2024) Best practice prescriptions for propagating and establishing pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) for timber production. Available at: https://www.futuretrees.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/ftt-monograph-oak.pdf (Accessed: 13 November 2025).

Garrick, L.D. and Lang, J.W. (1977) ‘Social signals and behaviors of adult alligators and crocodiles’, American Zoologist, 17(1), pp. 225–239.

International Oak Society (2014) Mating in Single Oaks. Available at: https://www.internationaloaksociety.org/content/mating-single-oaks (Accessed: 5 November 2025).

Mass Audubon (2023) ‘Why do some years produce more acorns than others?’. Available at: https://www.massaudubon.org/news/latest/about-those-acorns (Accessed: 5 November 2025).

Medem, F. (1981) Los Crocodylia de Sur America. Bogota: Biblioteca Jose Jeronimo Triana, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Murray, B. and Crother, B.I. (2017) ‘Additional details on temperature-dependent sex determination in Crocodylus acutus’, ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316927136 (Accessed: 13 November 2025).

Nature Picture Library (n.d.) Crocodylus acutus. Available at: https://www.naturepl.com/stock-photo-crocodylus-acutus-nature-image00556002.html?srsltid=AfmBOorgZtjhSasT0wDqleUdDVeAWo5O-P1LMx-vQH_BFX-9Zxrps1bx (Accessed: 12 December 2025).

Sax, H.J. (1930) ‘Chromosome numbers in Quercus’, Journal of the Arnold Arboretum, 11(4), pp. 220–223.

Season of Earth (2013) The incredible oak flower: how to identify oak flowers. Available at: https://seasonofearth.com/the-incredible-oak-flower-how-to-identify-oak-flowers/ (Accessed: 12 December 2025).

Schmidt, K.P. (1924) ‘Notes on Central American crocodiles’, Bulletin of the Field Museum of Natural History, Zoological Series, 12(6), pp. 79–87.

Srikulnath, K., Thapana, W. and Muangmai, N. (2015) ‘Role of chromosome changes in Crocodylus evolution and diversity’, Genomics & Informatics, 13(4), pp. 102–111. doi: 10.5808/GI.2015.13.4.102.

The Conservation Volunteers (2025) Quercus robur. Available at: https://www.tcv.org.uk/i-dig-trees-tree-library/common-oak/ (Accessed: 5 November 2025).

Varona, L.S. (1980) ‘Protection in Cuba’, Oryx, 15(3), pp. 282–284.

Woodland Trust (2025) Oak, English (Quercus robur). Available at: https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/british-trees/a-z-of-british-trees/english-oak/ (Accessed: 5 November 2025).